So, what is revenue? In simple terms, it’s the cash a business makes from selling its goods or services. But what about the money you get for work you haven’t done yet?

That, my friend, is a different beast altogether.

Imagine a client pays you upfront for a project. You see the money in your account and feel like you’ve already won.

But hold on. You just took out a loan from your customer that you have to pay back with your own work.

This is the world of unearned revenue, also known as deferred revenue. It’s the cash you’ve received for a promise – a promise to deliver goods or services at a later date. From the customer’s perspective, this is a prepaid expense, an asset. But for you, the seller? It’s a liability.

Why is Unearned Revenue a Liability?

It’s a liability because you owe something to your customer. You have an obligation to fulfill. Until you deliver that product or complete that service, the money isn’t truly yours to count as ‘earned’ income.

Misclassifying this cash as immediate revenue is a classic blunder that can seriously distort your financial statements, making your company look healthier than it actually is. It’s not just bad accounting; it’s misleading.

Now, let’s get into the nitty-gritty with some unearned revenue examples and the proper journal entries for them.

What is Unearned Revenue?

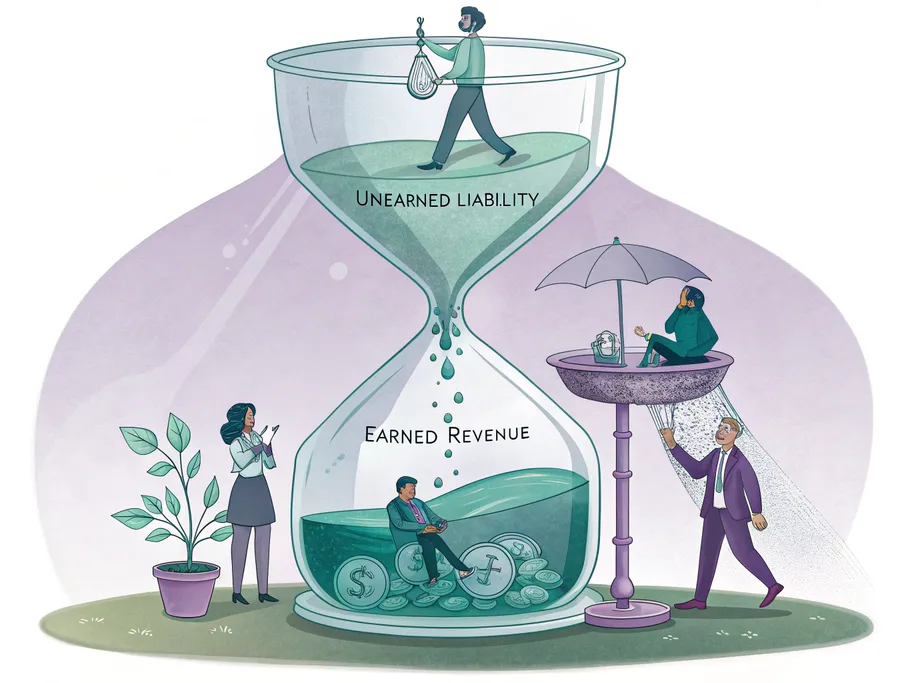

Unearned revenue is the cash you get from a customer before you’ve actually done the work. Think of it as a prepayment for goods or services you’ve promised to deliver down the road. You might also hear it called deferred revenue or prepaid revenue. For many businesses, getting paid upfront is standard practice, but here’s the catch: you can’t count that cash as earned income until you’ve held up your end of the bargain.

In the world of accounting, unearned revenue is not an asset or revenue, no matter how much you’d like it to be. Instead, it’s a liability. Why? Because you’re now indebted to your customer. You owe them something. You got paid upfront, so you’re rich, right? Nah, you just took out a loan from your customer that you have to pay back with your own work.

Common unearned revenue examples include:

- Prepaid insurance

- Airline tickets

- Annual software subscriptions

- Legal retainers

- Rent paid in advance

Getting that cash early is great for business. It boosts your cash flow, allowing you to pay off debt, buy more inventory, or just have the funds on hand to actually perform the service you were paid for. However, this financial cushion comes with a serious obligation. You must deliver what you promised, on time, to keep your customers happy and your business reputation intact. That’s why accounting for unearned revenue correctly as a liability is non-negotiable.

Unearned Revenue on the Balance Sheet

On a company’s balance sheet, you’ll find unearned revenue listed as a current liability. It’s a debt owed to a customer, and since it’s typically expected to be settled within a year, it lives under the “current liabilities” section.

If you mess this up and record unearned revenue as actual revenue right away, you’re cooking the books. Your profits will look artificially inflated in the short term, and then understated in the periods when you actually earn the money. This also violates the matching principle, a fundamental accounting rule stating that revenues and their related expenses must be recorded in the same period.

So, always record it as a liability first. The only exception is if the service or product is due 12 months or more after the payment date, in which case it becomes a long-term liability.

How to Calculate Earned Revenue

As time passes and you start delivering the goods or services, you can begin recognizing a portion of that unearned revenue as earned revenue. The calculation is straightforward.

Let’s say a client pays you $12,000 for six months of consulting services. To figure out your monthly earned revenue, you just divide the total payment by the number of months.

$12,000 / 6 months = $2,000 per month

Each month, you’ll make an unearned revenue adjusting entry to move $2,000 from the unearned revenue (liability) account to the service revenue (revenue) account. This process continues until the full amount has been earned and the liability is cleared.

Unearned Revenue Journal Entry Examples

Alright, let’s get into the numbers. Since unearned revenue is a liability, its initial journal entry is a credit. Congratulations, you got paid upfront, but you didn’t earn money – you just took out a loan from your customer that you have to pay back with your work.

Here’s how it works: When the cash hits your account, you debit Cash (because your assets increased) and credit Unearned Revenue (because your liabilities increased). This entry shows you have more cash, but you owe a service or product for it.

Later, once you’ve actually delivered the goods or performed the service, you’ll make an unearned revenue adjusting entry. You’ll debit the Unearned Revenue account (to decrease the liability) and credit your Revenue account (to finally recognize the income you’ve earned).

Let’s walk through a few common unearned revenue examples to see how the journal entries play out.

Rent Payments Made in Advance

A classic example. A landlord receives $12,000 from a tenant for a full year’s rent upfront. This isn’t income yet; it’s a liability until each month passes.

First, the landlord records the initial cash receipt:

| Account | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|

| Cash | $12,000 | |

| Unearned Rent Revenue | $12,000 | |

| To record receipt of advance rent payment |

Each month, the landlord earns 1/12th of that revenue:

$12,000 / 12 months = $1,000 per month

So, at the end of each month, the landlord makes this adjusting entry to recognize the earned portion:

| Account | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|

| Unearned Rent Revenue | $1,000 | |

| Rent Revenue | $1,000 | |

| To recognize one month of earned rent |

Services Contract Paid in Advance

Imagine a contractor gets paid $100,000 for a project that will take ten months to complete. That entire sum is unearned until the work is done.

The initial journal entry to record the payment is:

| Account | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|

| Cash | $100,000 | |

| Unearned Service Revenue | $100,000 | |

| To record prepayment for a 10-month project |

The amount earned each month is:

$100,000 / 10 months = $10,000 per month

As each month of work is completed, the contractor will record the earned revenue:

| Account | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|

| Unearned Service Revenue | $10,000 | |

| Service Revenue | $10,000 | |

| To recognize one month of earned service revenue |

Prepayment for Newspaper Subscriptions

Subscription models are all about unearned revenue. A publishing company receives $1,200 for a one-year newspaper subscription.

Here’s the entry when the customer pays:

| Account | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|

| Cash | $1,200 | |

| Unearned Subscription Revenue | $1,200 | |

| To record a one-year subscription payment |

If the newspaper is delivered monthly, the company earns $100 each month ($1,200 / 12 months). After each delivery, they make the following entry:

| Account | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|

| Unearned Subscription Revenue | $100 | |

| Subscription Revenue | $100 | |

| To recognize one month of subscription revenue |

Key Takeaways

So, let’s be brutally honest. Unearned revenue isn’t an asset; it’s a financial IOU. It’s a promise you’ve been paid for but haven’t kept yet. While that cash is great for operations and investments, it’s technically a debt to your customer.

Recording it properly as a liability on your balance sheet isn’t just good practice – it’s required. It gives a true picture of your company’s future obligations and expected revenue. If you don’t, you’re not just messing up your books; you’re violating fundamental accounting principles (like GAAP), which is a fantastic way to find yourself in a world of trouble. So, recognize it as the liability it is, do the work, and then, and only then, can you call it revenue.