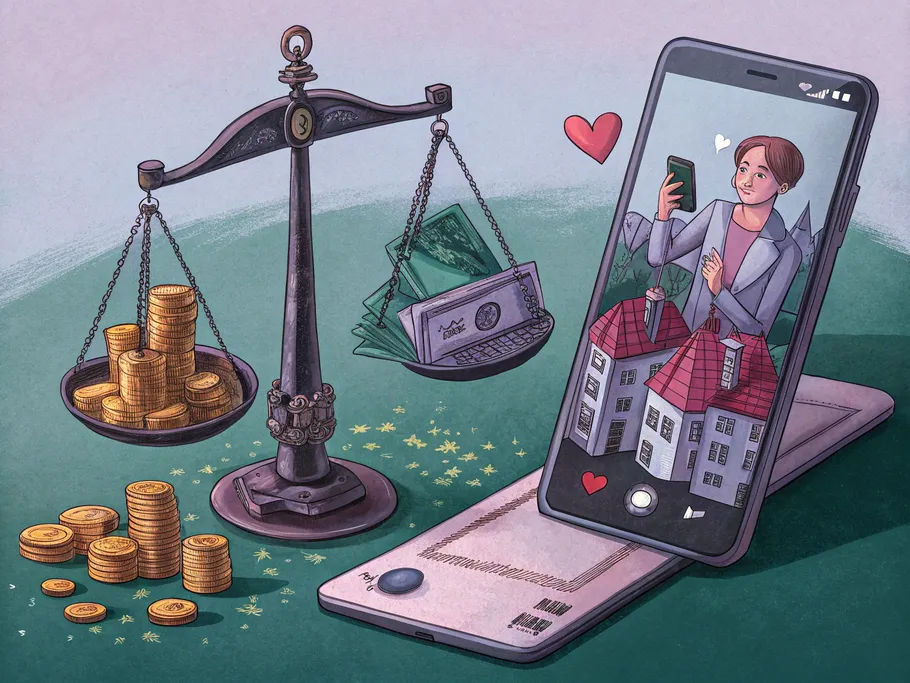

Ever wonder what a balance sheet actually is?

Think of it as a financial selfie. It’s a snapshot of your company’s financial health at a single, specific moment in time, showing what you own (assets), what you owe (liabilities), and what’s left in the middle (equity).

It’s one of the big three financial statements, alongside the income statement and the cash flow statement. Its official, grown-up name is a statement of financial position, which is a fancy way of saying it shows you where the company stands, right now.

But here’s the catch – and one of the key limitations of a balance sheet – it’s not the whole truth. Assets are often listed at their original historical cost, not their current market value. That piece of land bought for $50,000 in 1985 might be worth millions today, but on the balance sheet, it’s still stuck in the past. It also completely ignores priceless intangible assets like your brand’s stellar reputation or your team’s genius, giving you an incomplete picture.

What is an Accounting Period?

Debating the finer points of your “accounting period” – whether it’s a calendar, fiscal, or natural business year?

Spoiler alert: it’s just the taxman’s arbitrary deadline for you to prove you’re not a criminal.

This is the timeframe where all your company’s financial transactions are recorded and bundled up. The date you see on a balance sheet is the final day of that period. It’s a hard cutoff, meaning every transaction up to the last second of that day has been accounted for, for better or for worse.

The 3 Core Components of a Balance Sheet

The balance sheet is built on a beautifully simple foundation of three parts: assets, liabilities, and equity. Let’s pull back the curtain on each one.

Assets (What You Own)

Calling everything you own an “asset”?

If it can’t be converted to cash, it’s a liability in denial.

More formally, an asset is anything, physical or not, that a business owns and can be turned into cash. Think company cars, computers, buildings, and machinery. These are your tangible assets. The non-physical ones you can’t see or touch are your intangible assets.

For something to officially make it into the assets column, it has to check a few boxes:

- It must be purchased or donated.

- It needs to have a future economic value that you can actually measure in dollars and cents.

- Prepaid expenses (like paying for a year of insurance upfront) also count here.

Types of Assets on the Balance Sheet

Assets are split into two camps: the sprinters and the marathon runners.

Current Assets

These are the short-term assets, the stuff you can easily convert into cash within a year.

Cash and cash equivalents This is your checking account balance, petty cash, and any checks you’ve received but haven’t deposited yet.

Why is cash listed first on a balance sheet? Because cash is king. It’s the most liquid asset you have, meaning it’s already cash. The balance sheet lists assets from most liquid to least, so cash naturally takes the top spot. It’s the quickest indicator of a company’s ability to pay its bills.

Cash equivalents are super short-term investments that mature in three months or less, like money market funds or 90-day government bonds. Their value isn’t likely to bounce around.

For example, if The Financial Falconet Inc. starts the business by investing $8,000 in cash, the journal entry is a debit to the CASH account and a credit to the CAPITAL account. Here’s how it looks:

Accounts receivable This is the pile of IOUs from your customers. It’s the money people owe you for goods or services already delivered. This line item often includes an “allowance for doubtful accounts,” which is a fancy way of saying, “we know some of you aren’t going to pay up.”

Inventory This covers your raw materials, works-in-progress, and finished goods ready for sale. For instance, if Finance Inc. drops $3,000 in cash on computer accessories, the cash account goes down, and the inventory account goes up by the same amount. Here’s the visual:

Prepaid expenses These are costs you’ve paid for in advance but haven’t used up yet. Think of things like insurance, rent, or advertising contracts.

Example: Let’s say you pay $3,000 in March for a full year of property insurance ($250/month). By the end of June, you’ve used up four months, or $1,000 worth. If you create a balance sheet then, the remaining $2,000 is listed as a prepaid expense.

Non-Current Assets

These are the long-haul assets, the things you don’t plan on converting to cash within a year.

Investments This includes long-term investments in securities, real estate, or other businesses, as well as restricted funds like a bond sinking funds (money set aside specifically to retire bonds).

Property, Plant, and Equipment (PPE) This is the heavy stuff: buildings, land, furniture, and machinery. It’s important to note that land is recorded at its purchase cost and isn’t depreciated, because, well, it’s land. However, improvements made to the land, like paving a parking lot, are depreciated over their useful life.

Intangible assets “Some of the deepest wealth is not created, but discovered.”

He built his walls with stone and tallied his gold, believing true worth lay in what he could touch. Yet, his empire’s silent strength came from the ancient wisdom he embraced, the trust he inherited, and the name whispered with reverence, not forged by his own hand. These were the unseen pillars, recognized and claimed from the world’s deep currents.

In business, these are your trademarks, goodwill, patents, and copyrights. The key rule is that only acquired intangible assets (the ones you bought) are listed on the balance sheet, not the ones you developed internally.

Liabilities (What You Owe)

Ah, liabilities. This is the constant, soul-crushing drip of rent, wages, and taxes that reminds you “profit” is just a temporary illusion before the next bill arrives.

These are your company’s debts and financial obligations. Just like assets and liabilities, they’re split into two categories, and the current ones are listed by their due date – the most urgent ones first.

Current Liabilities (Short-Term Liabilities)

These are the debts you need to settle within one year. Think taxes, salaries, credit card debt, and money owed to suppliers (accounts payable). This also includes the current portion of long-term debt. For example, if you have a 10-year loan with two payments due this year, those two payments are a current liability, while the rest of the loan is a long-term liability.

Accounts payable This is your tab with your suppliers. It’s what you’ve bought on credit and typically need to pay back within 30 days.

If a company named Duzzlag buys $2,700 worth of tools on credit, its inventory (an asset) goes up, and its accounts payable (a liability) goes up by the same amount. The balance sheet stays balanced:

Taxes payable This is the money you owe the government that hasn’t been paid yet. It includes all unpaid taxes like sales tax and income tax.

Accrued expenses These are expenses you’ve incurred but haven’t been billed for yet. Think of employee salaries earned but not yet paid out, or interest on a loan that’s accumulated but isn’t officially due.

Deferred revenue Oh, you mean getting paid for a promise? Deferred revenue is the cash customers give you for goods or services you haven’t delivered yet. It’s a liability because, shockingly, you’re expected to actually do the work you were paid for. Once you deliver, it magically transforms from a liability into revenue.

Interest expense This is any accumulated interest you owe on your debts, also known as interest payable.

Non-Current Liabilities (Long-Term Liabilities)

These are the obligations you don’t have to pay off for at least a year. This includes things like long-term loans, bonds, and pension fund obligations.

Pension fund liability This is the money a company is obligated to pay into its employees’ retirement accounts.

Deferred tax This is a tax that is assessed in the current period but won’t be paid until a future one. It’s recorded as a liability because the bill will eventually come due.

Dividends payable If a company has officially declared it will pay dividends to its shareholders but hasn’t cut the checks yet, that amount sits here as a liability.

Equity (What’s Left for the Owners)

Before a kingdom stands, there is the first stone laid, the first coin offered by those who believe. This is the heart of what is built, the silent claim of ownership. It is not a burden, but the very essence of worth, held in trust for those who gave, a promise of what will rise.

The true measure of wealth is not what you possess, but what you build.

In less poetic terms, equity is the money put into the business by its owners or shareholders, plus all the profits the company has generated and kept. While assets and liabilities are split into current and non-current, equity accounts are a bit different. They primarily consist of capital contributions and retained earnings.

The main equity accounts you’ll see are:

- Common stock

- Retained earnings (the profits reinvested back into the company)

- Treasury stock

- Additional paid-in capital

Putting It All Together: How to Read a Balance Sheet

So, let’s “explain” the balance sheet in the simplest terms.

On one side, you have Assets – a neat list of everything you own.

On the other side, you have Liabilities and Equity – a brutally honest list of everyone you owe money to, which, surprise, also includes the owners (that’s the equity part).

Relying on your balance sheet to track earnings and spending?

That’s like using a photo of your fridge to explain your diet. You’re looking at the wrong damn thing. For that, you need an income statement.

Order of Items on the Balance Sheet

Everything is listed in order of liquidity. The accounts that can be turned into cash the fastest, like cash and inventory, are listed first. The stuff that’s harder to sell, like plant, property, and equipment, sits at the bottom.

The Holy Trinity: The Balance Sheet Equation

Ah, the accounting equation. It’s the universe’s way of reminding you that for every shiny new asset you acquire, a corresponding piece of your soul (or your bank account) must be sacrificed to the gods of debt or ownership. It’s not a suggestion; it’s cosmic law.

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

This is the one rule to rule them all. The total amount in all your asset accounts must equal the total amount in all your liability and equity accounts. If they match, the sheet is balanced. If they don’t, something is deeply, deeply wrong.

It just makes sense. To get assets, a company has to pay for them. It can either use its own money (equity) or use someone else’s money (liabilities). There is no third option.

Bookkeeping: The Art of Not Screwing Up

Understanding the accounting equation is step one. Step two is learning how to record the transactions that make it all work. This process is called Bookkeeping.

It runs on a system called double-entry, where every single transaction gets recorded in two places. For every credit, there must be an equal and opposite debit. This is the system of debits and credits that keeps the financial universe in balance.

Why is Double-Entry Bookkeeping So Important?

Oh, you thought you could just jot down numbers wherever you felt like it? How adorable.

Double-entry bookkeeping is the adult supervision your finances desperately need. It’s a revolutionary system where—get this—the numbers have to match. If they don’t, it means you’ve messed up. Shocking, I know.

It’s a built-in error detection system. Since every debit needs a matching credit, the two columns must always be equal. If they aren’t, you know instantly that you’ve made a mistake somewhere. It’s the financial equivalent of having two people count the money. If they come up with different numbers, you don’t leave the room until you figure out why.

The Simple Rules of Debits and Credits

Think of your books like a gentle seesaw. Every transaction has two sides, and the goal is to keep things perfectly level. It’s a quiet rhythm, not a harsh set of commands.

When assets rise on one side (a debit), liabilities or equity must rise on the other (a credit) to keep it level. When assets fall (a credit), something on the other side must fall too (a debit).

Here are the unbreakable rules:

- An INCREASE in ASSETS is a DEBIT.

- A DECREASE in ASSETS is a CREDIT.

- An INCREASE in LIABILITIES or EQUITY is a CREDIT.

- A DECREASE in LIABILITIES or EQUITY is a DEBIT.

That’s it. To put it even more simply: Assets go up with a Debit. Liabilities and Equity go up with a Credit.

Balance Sheet Analysis: The Fun Part

The balance sheet isn’t just a static document; it’s a goldmine of data you can use for balance sheet analysis. This is how to analyze a balance sheet to see what’s really going on under the hood.

Here are a couple of the big ones.

The Debt-to-Equity Ratio (D/E Ratio)

The debt-to-equity ratio shows how much a company relies on debt to finance its operations. But a “good” D/E ratio is highly industry-dependent. Capital-intensive industries like utilities often have ratios around 2.0, which is perfectly normal given their massive infrastructure costs. Meanwhile, tech companies, with fewer physical assets, might have a D/E ratio closer to 0.5. A high ratio isn’t automatically bad; it just means the company is using leverage, which can be risky but also profitable.

Acid-Test Ratio (Quick Ratio)

Also known as the quick ratio, this is a type of liquidity ratio that answers a simple question: can this company pay its short-term bills right now with its most liquid assets? Lenders absolutely love this metric because it cuts through the noise and shows a company’s immediate ability to cover its ass.

Oh, you have more assets than liabilities? Congratulations, you’ve cleared the incredibly low bar of not being technically insolvent. Here’s your ‘Financially Healthy’ sticker.

The Bottom Line

So, what is a balance sheet? At its core, it’s a snapshot of your company’s financial health at a specific moment in time. It’s a summary of what your business owns (assets), what it owes (liabilities), and what’s left over for the owners (equity).

It’s a “vital” record, mostly so you can pretend your financial position isn’t a house of cards, at least until the next audit.

Jokes aside, understanding tools like this helps you get a clear picture of where you stand. There is a quiet power in seeing your financial position honestly. This clarity allows you to make thoughtful choices, one step at a time.